EDITOR, INTERNATIONAL NEWS

NBC News, London, October 2023–August 2025

I edited news and features and for NBC News’ international desk in London, with a focus on the conflicts in the Middle East. I also worked across the newsroom to respond to breaking news, from natural disasters, to assassinations and elections.

MERCHANTS OF CARE

Type Investigations and The Pulitzer Center

—Winner, Hillman Prize for investigative journalism, 2024

—Honorable mention, John Bartlow Martin award for magazine journalism, 2024

—Finalist, investigative and general reporting award, NIHCM Foundation, 2024

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, from February to April 2020, the US healthcare sector shed more than 1.5 million jobs—nearly 10% of the total healthcare workforce at the time. And the nursing shortage is set to grow significantly worse in the coming years.

To bolster their workforces, hospitals in the US and Europe have dramatically accelerated hiring from countries like the Philippines, India, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Jamaica. What was once a steady trickle of nurses leaving their home countries has become a flood.

Quartz, in partnership with Type Investigations and with support from the Pulitzer Center, traveled to India, Nigeria, the Philippines, the United Kingdom, and the United States to investigate the consequences of this global movement of nurses. We spoke with nurses, recruitment agency employees, hospital officials, public health experts, government health agencies, and researchers. Our investigation found an international bidding war for healthcare workers, yielding opportunities for some nurses but exposing others to exploitation—and leaving poorer health systems scrambling to cope.

SENIOR REPORTER, global economy

Quartz, London and Bangkok, September 2021–August 2023

I covered economic disruption in the wake of pandemic, war and the climate crisis, writing clear, quick explanatory articles, analyses and investigations with a focus on the supply chain crisis, labor and the climate economy.

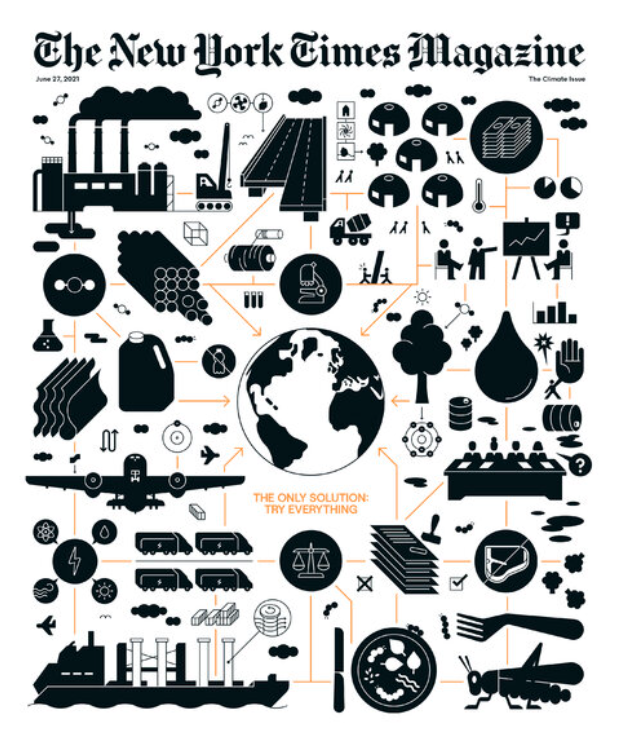

GREENING THE WAVES: CAN MASSIVE CARGO SHIPS USE WIND TO GO GREEN?

The New York Times Magazine

Climate change, Allwright told anyone who would listen, would create intolerable pressures. He would point them to books and reports by scientific organizations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that outlined what would happen if the world stayed on its current trajectory, sending average temperatures up 3 degrees or more: vicious wars over resources, mass refugee migrations, major cities engulfed by rising seas. And because this was a crowd of businesspeople, he would mention, too, that all of that would be catastrophic for the economy.

This preaching of sustainability was heard, at first, as an act of aggression. Shipping executives would walk out of meetings and slam the doors as they left. When he brought up numerical targets for carbon-dioxide emissions from shipping, someone shouted that it would never happen. “It’s a fantasy!” another yelled. Then, in the last couple of years, something shifted. The industry has been facing more pressure to emit less carbon, but one of the most talked-about methods of reducing shipping’s carbon footprint — using alternative fuels such as hydrogen — is costly and difficult to pull off. Wind propulsion, on the other hand, is already available.

The Lonely and Dangerous Life of the Filipino Seafarer

The New York Times

ABOARD THE UBC CYPRUS IN THE NORTH PACIFIC — On his first ocean voyage seven years ago, Jun Russel Reunir was sent deep into the bowels of a cargo ship, where he shoveled iron ore until his muscles ached — then continued shoveling for a dozen hours more.

“I cried in my cabin three times that month,” Mr. Reunir said.

Filipinos like Mr. Reunir, now 27, have for decades powered the global shipping industry, helping to move 90 percent of global trade.

A few months ago, he and 18 other Filipino men crewed a cement carrier traveling from Japan to the Philippines.

For a visitor along for the ride, the ocean voyage meant fresh sensations. The sound of the waves drowned out by the roar of the engines. The deck scattered with dead flying fish after a storm. The breeze filled with the smell of cheap bunker fuel.

But for the seamen, perhaps the only thing worse than the repetitive drudgery of their harsh labor was the boredom that came when they were done, any romance with the sea long since faded.

Women on the Move

National Geographic Magazine

A 31-page, six-continent story published in the February 2021 issue of the magazine that delves into different facets of women’s migration experiences. I interviewed women across the world, including a Somali pastoralist driven from her land by drought and climate change, a Vietnamese woman staking her future on a stranger in Singapore who she met through a marriage broker, and a young woman born into the Hazara diaspora in Pakistan, obsessed with K-pop and dreaming of moving to South Korea.

PORT IN A STORM

Nikkei Asia

For the global shipping industry, chaos began with the tap of a million "buy now" buttons.

In the second half of 2020, Americans, trapped at home by the pandemic, started buying weighted blankets, Crocs, giant fleece hoodies, ring lights and desks at a relentless pace. One toilet paper manufacturer saw a 600% increase in sales over two weeks. Another retailer sold out of a year's stock of bird feeders in two months. Yoga leggings, milk frothers, air fryers and lawn mowers were crammed into shipping containers in the ports of Asia.

Earlier that year, at the start of the pandemic, idled ships could be seen anchored off the Singapore coast, eerie and still. But by the fall, they were idle no more: Container vessels steamed across the Pacific, carting goods from China so busily that they became snarled in traffic in California's San Pedro Bay. By January 2021, as many as 30 ships were anchored off the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, waiting to pull into berth.

Read story (PDF)

On Pandemic’s Front Lines, Nurses From Half a World Away

The New York Times

There were seven nurses in the Buendia family. One of them, Jhoanna Mariel Buendia, got a call from the Philippines on March 28, just before the start of her shift at an intensive care unit in a British hospital.

It was her father, with the news that her beloved aunt — an I.C.U. nurse, in Florida — had died of complications from Covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

Ms. Buendia, 27, went to work. She suited up, strapping on her N95 mask, face shield, gown and apron and taping down her gloves, too numb to process the fact that her aunt had lost her life doing what she was about to do. It wasn’t until a few hours later, as she tended to a patient suspected to have the virus, that it became real and she burst into tears.

Nurses from the Philippines and other developing countries have long made up for shortages in wealthier Western nations. They now find themselves risking their lives on the front lines of a pandemic, thousands of miles from home.

Trapped by Pandemic, Ships’ Crews Fight Exhaustion and Despair

The New York Times

Ralph Santillan, a merchant seaman from the Philippines, hasn’t had shore leave in half a year. It has been 18 months since he reported for duty on his ship, which hauls corn, barley and other commodities around the world. It has been even longer since he saw his wife and son.

“There’s nothing I can do,” Mr. Santillan said late last month from his ship, a 965-foot bulk carrier off South Korea. “I have to leave to God whatever might happen here.”

His time on the ship, where he spends long days chipping rust off the deck or cleaning out cargo holds, was supposed to have ended in February, after an 11-month stint — the maximum length for a seafarer’s contract.

But the Covid-19 pandemic led countries to start closing borders and refusing to let sailors come ashore. For cargo ships around the world, the process known as crew change, in which seamen like Mr. Santillan are replaced by new ones as their contracts expire, ground nearly to a halt.

In June, the United Nations called the situation a “growing humanitarian and safety crisis.” And there is still no solution in sight.

Crony capital: How Duterte embraced the oligarchs

Nikkei Asian Review

MANILA/DAVAO, Philippines — The day Rodrigo Duterte became president, Roberto Ongpin was one of the Philippines' richest men. Ongpin had survived — and prospered — under six presidential administrations by trading favors and greasing friendships with politicians. He had a full arsenal of luxuries at his disposal, including a billionaire's island dotted with villas, serviced by butlers and accessible by a fleet of private jets, and an exclusive club at the center of the capital's business district, where the whiskey was poured each day at precisely 5 p.m. and far into the night.

During his populist campaign for president in 2015 and 2016, Duterte took aim at the corruption and excesses of wealth-hoarding ruling families like Ongpin's. He called them "a cancer on society," and "illustrious idiots" who flew around in private planes while the Filipino people suffered.

Then, just four days into his term, Duterte unloaded. "The plan is to destroy the oligarchs embedded in the government," he said. "I'll give you an example publicly: Ongpin, Roberto."

Read story (PDF)

why the philippines has so many teen moms

NPR News

—Human Rights Press Award for explanatory feature writing, 2021

At 12 years old, Joan Garcia liked leaping into the sea and racing the boys to the nearest pylon. She liked playing tag. When she started having sex at 13, she thought it was just another game. Joan was skipping across the pavement, playing a game with friends, when an older neighbor noticed her rounding belly.

Her daughter, Angela, is now a year old. Joan crouched on the floor, folding up her lanky teenage limbs and fed Angela fingers-full of steamed rice, crimped strands of instant noodles and fermented anchovies from the family's small communal bowl.

Joan, now 16 years old, said that since she became a mother, she's embarrassed to play kids' games, then paused for a moment. "Sometimes I still play tag in the water with my brothers," she admitted.

Where 518 Inmates Sleep in Space for 170, and Gangs Hold It Together

The New York Times

—Human Rights Press Award for explanatory feature writing, 2020

MANILA — For some inmates of the Manila City Jail, making the bed means mopping up sludgy puddles, unfolding a square of cardboard on the tile floor and lying down to sleep in a small, windowless bathroom, wedged in among six men and a toilet.

On one recent night at the jail, in Dorm 5, the air was thick and putrid with the sweat of 518 men crowded into a space meant for 170.

The inmates were cupped into each other, limbs draped over a neighbor’s waist or knee, feet tucked against someone else’s head, too tightly packed to toss and turn in the sweltering heat.

Since President Rodrigo Duterte’s violent antidrug campaign began in 2016, Philippine jails have become increasingly more packed, propelling the overall prison system to the top of the World Prison Brief’s list of the most overcrowded incarceration systems in the world.

In the Manila City Jail, sleep is the most precious commodity.

BLOOD AND POWER IN THE PHILIPPINES

The FRONTLINE Dispatch on FRONTLINE PBS

—Nominated for a George Polk award

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte makes his own rules. His war on drugs has led to the deaths of thousands of alleged drug users and dealers. His violent rhetoric and rape jokes have shocked people around the world. Yet he’s hugely popular. Reporter Aurora Almendral delves into what made him the leader he is today. Her investigation starts in his hometown in the Philippines.

33 minutes

THE KILL LIST

NBC News

—Winner, Overseas Press Club of America Award for best international reporting in the broadcast media

—National Headliner Award for online video

—Human Rights Press Award for broadcast video

—Pictures of the Year International Award for documentary video

In the Philippines, thousands have died in the government-induced slaughter. It is in the closeness and intimacy of the camera — as it traces the ligature marks along the wrists of a bullet-riddled corpse, capturing the ebbing tears of a family as they gradually accept that the body they hold will never wake up, and filming the nervous laughter of a drug addict as he asks a police officer not to be killed — that the complex issues of crime and state play out.

Filmed one year after Duterte assumed the presidency, we gained unprecedented access to the lives of survivors and policemen, and considered why Duterte’s bloody rampage continues: from the normalization of government-inspired brutality, the narrative of righteousness that undergird the killings, to the validating effect of President Donald Trump’s unequivocal support of the Philippine president.

The documentary shows how citizens of a country are willing to compromise their morals for what they’ve been convinced is the greater good and sheds light on an ongoing human rights crisis, serving as a cautionary warning on a dark side of the human condition.

22 minutes

breaking news

As the Philippines reporter-producer for NBC News, I cover breaking news on the ground, including typhoons, landslides, volcanic eruptions, mass shootings, a woman’s brazen attempt to smuggle an infant out of the country, as well as global events, like tensions in the South China Sea or the meeting between presidents Donald Trump and Rodrigo Duterte.

I’ve also covered breaking news events for The World, Frontline PBS, The New York Times, National Geographic, NPR News and The Nikkei Asian Review.

Brazen Crocodile Preys on a Philippine Town: ‘It Was Like He Was Showing Off’

The New York Times

BALABAC, Philippines — On the November day when Cornelio Bonite disappeared, a crocodile was spotted in the water with a human arm clasped in its jaws.

“It was like he was showing off,” said Efren Portades, 67, a watchman in the town of Balabac, a marshy island community in the Philippines near the sea border with Malaysia, who led the search for Mr. Bonite, a 33-year-old fisherman.

The month before, another crocodile — or the same one, for all anyone knows — had grabbed 16-year-old Parsi Diaz by the thigh after she jumped into the bay for a swim. She escaped.

The year before that, a 12-year-old girl had been attacked while crossing a river. A few months later, that girl’s uncle was ripped in two.

And more dogs and goats than anyone could count had been snatched from Balabac’s shores.

Some people were ready for revenge.

'If the camel is fine, our life is fine.' But Somali camel herding is in jeopardy.

National Geographic

XIJIINLE, SOMALILAND—Some camels on the beach lay splayed on their sides like sleeping cats. Others hoisted themselves up on their long legs, blinking at the brightening dawn sky. Others loped across the sand as curly-haired calves frolicked in playful loops or teetered on spindly legs, bellowing for milk.

Xijiinle is a coastal settlement of about 200 seminomadic pastoralists in Somaliland, an autonomous region of northern Somalia. The village lies at the end of a dirt road that runs 200 miles from Hargeysa, Somaliland’s capital, through a rugged landscape of dry brush, dusty gullies, and open meadows, greened from recent rain. Hamlets like this, with their domed huts made of gathered branches and draped cloths, are centers of an age-old camel herding tradition.

Clinging to Life, Love and a Foothold on Manila’s Crumbling Piers

The New York Times

MANILA — The fishing is best on nights like this when the moon is a sliver in the sky, and at midnight in the Philippines’ largest fishing port, the atmosphere was frenetic.

Dockworkers in thick rubber boots emptied the catch from the rusting vessels crowded against the pier. Into hundreds of plastic pails lined up in rows, they tossed grouper, barracuda, tuna, flying fish, moonfish and sardines: 300 tons of fish on an average day.

Women in slime-streaked aprons, pockets stuffed with cash, shouted orders and negotiated prices, and the returning fishermen soon had money to spend in the nearby bars and brothels.

Inside the port is one of Manila’s most notorious slums, Market Three, which has a reputation in the capital as a lair for drug dealers and hit men willing to kill someone for $100.

How The Pandemic Has Upended The Lives Of Thailand's Sex Workers

NPR News

They were all working harder and earning less, N. says. There were about a dozen women at each of the Soi 6 bars that managed to stay open, fewer than before, but far outnumbering the foreign customers, most of whom were expats living in Pattaya or visitors from Bangkok.

"Boys, boys, boys, where are you going," the women said as a couple of men strolled by. "I love you!" they yelled at strangers. They pretended to swoon and called every passing man handsome. One woman, tilting on her stilettos, tugged with her full might at a man's arm to pull him in and perhaps oblige him to buy her a shot. He wrestled his arm free and walked on.

These LGBTQ+ migrants imagined a better life in the U.S.—did they find it?

National Geographic

In Honduras, Alexa said, she often prayed for protection and luck at her altar to Santa Muerte, where she kept a figure of the saint on a stack of dollar bills encircled by flickering candles, a bottle of perfume, and offerings of chocolate bars, marshmallows, and gummy candies. She doesn’t have an altar in Memphis. “My life is too unstable for that,” she said.

In San Pedro Sula, she could talk to friends and laugh off her problems, but in Memphis, she said, everyone shuts themselves into their homes at night. She longs to hug her mother. She said she and Norlan were fighting constantly, and the others in the house wanted them to leave. She wanted to go to Dallas, Texas, to live with her sister but said she didn’t have enough money to buy a bus ticket.

When I asked Alexa if she ever thinks she shouldn’t have come to the U.S., she looked at me with soft incredulity. “Yes, of course.”

LABORS LOST

Nikkei Asian Review

Thousands of Filipinos work in hotels and casinos from Las Vegas to Macao and Phnom Penh. Filipinos are nurses and doctors in Milan, Jiddah and Miami. Some 400,000 work aboard cruise ships or cargo ships, where they make up the largest share of any one nationality in the industry. They are engineers at oil refineries and nannies in homes. At airports from Singapore to San Francisco, Filipinos handle baggage, man security and staff customer service desks. When weary travelers transit through the once-bustling airport of Dubai, there's a good chance the person serving them coffee is Filipino.

The pandemic has highlighted how much the global economy depends on migrant labor, and how countries have treated their migrant populations as disposable resources. Migrants are struggling with indefinite furloughs and lost jobs; they are being neglected by institutions and face rising xenophobia in many countries. Despite the contributions they have made to the countries where they work -- often at great personal cost -- and even though their labor will be critical to the economic recovery of their host countries, few governments have proved willing to help them through this crisis.

"The pandemic has made existing inequalities worse," said Itayi Viriri, a spokesperson for the International Organization for Migration, a United Nations agency. If migrants are left behind, the "social and economic consequences for both countries of origin and destination may be more severe and protracted."

the dark side of thailand’s coronavirus success

NPR News

In April, Somsri Taenmok, 41, drifted into Thamniyom temple in Ayutthaya, a city an hour north of Bangkok, holding the hand of his 5-year-old daughter, Anna. He was a day laborer looking for work. For two days, he wandered through the city visiting construction sites, but projects had slowed down and no one needed an extra hand. At night, he and his daughter slept on a borrowed blanket under an awning in the temple parking lot. The caretaker, Swing Wajapairoh, 82, remembered him as a quiet man. His daughter, she said, was hip-high and talkative.

"Father don't leave me" was the last thing people nearby heard the girl say. Their bodies were recovered later that day. They were 200 miles from their home province of Maha Sarakham. While no one can say for sure what the reasons are for Taenmok's death, suicides like his, occurring amid the stresses of the economic downturn, have alarmed many, including the government.

for these women, an age-old way of life is ending in the horn of africa

National Geographic

SOMALILAND—Guude’s home village, Topta, in northern Somaliland, was abandoned after the drought in 2016. She now lives a two-hour walk away in Hijiinle, near Lughaya, on the north coast, where she depends on humanitarian aid and the generosity of relatives. She moved there after her herd of 70 goats and sheep died.

Back when it rained reliably in Topta, Guude recalled, the trees grew, and the animals ate. She would wake up in the morning to green fields dotted with wildflowers and frolicking goats. The villagers plucked kulan, a bittersweet fruit, from the trees, and when their camels ate the kulan, their milk became sweeter. Families had milk and butter and enough meat for everyone. No one had to go to other towns begging for food.

They didn’t know it at the time, Guude said, but their life in Topta was happiness defined. “That is what I miss the most,” she said. “Everything.”

bombings in Sri lanka

I covered the immediate aftermath of the coordinated bombings in Sri Lanka that targeted churches and hotels on Easter Sunday 2019, killing over 250 people. I arrived in Colombo on the evening the bombings occurred and filed fives stories in six days during the breaking news phase. My reporting led the program at PRI’s The World.

what’s next for these transgender asylum seekers stranded in mexico?

National Geographic

TIJUANA, MEXICO—Kataleya Nativi Baca, 29, can see the yellow grasslands of San Ysidro, California, from the crests of Tijuana’s hills. The palm trees swaying less than a mile from her shack are rooted in the place she calls el otro lado—the other side. When she goes to the beach in Tijuana, the sands of San Diego are an arm’s reach away through the narrow gaps between the 20-foot-tall steel bollards of the border wall. But for Kataleya, the United States has never felt farther away.

For domestic workers, apps provide solace—but not justice

Rest of World

Their distance from home and isolation have made migrant domestic workers into eager adopters of technology. They raise children living thousands of miles away over video calls and commiserate over long chat messages with other domestic workers whom they may never meet in person. In lively Facebook groups, they run sideline businesses selling food from their home countries, help one another parse labor contracts, and trade tips on using pressure cookers. They exchange memes about washing laundry as well as selfies from hikes. But desperate pleas for help are also common: What do I do if I’m not being paid? What will happen to me if I try to escape? Many share news articles about domestic workers: a woman in Kuwait starved and murdered by her employers, another who leapt off a high-rise building to her death.

duterte’s luster dulls as rice prices soar in philippines

The New York Times

MANILA — Through controversy after controversy, President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines has always been able to count on his appeal among the nation’s poor. But soaring prices for staples like rice are starting to alienate that vital base of support.

During his presidency, Mr. Duterte has clashed with cherished institutions like the Roman Catholic Church, made jokes about rape and led a brutal war on drugs that has left thousands dead.

But he now faces deepening discontent in an area that particularly affects the urban poor: the price of food.

The country’s inflation rate has hit a nine-year record — 6.7 percent — after climbing for nine consecutive months, the Philippine Statistics Authority said last week. That situation is bad enough that on Tuesday Mr. Duterte ordered restrictions dropped on the importing of rice, ending a decades-old protectionist policy administered by the country’s National Food Authority.

AT 100 OR SO, SHE KEEPS A PHILIPPINE TATTOO TRADITION ALIVE

The New York Times

BUSCALAN, Philippines — She wakes up every morning at dawn and mixes an ink out of pine soot and water. She threads a thorn from a bitter citrus tree into a reed, crouches on a three-inch-high stool and, folded up like a cricket, hand-taps tattoos onto the backs, wrists and chests of people who come to see her from as far away as Mexico and Slovenia.

The woman, Maria Fang-od Oggay, will finish 14 tattoos before lunch — not a bad day’s work for someone said to be 100 years old. Moreover, she has single-handedly kept an ancient tradition alive, and in the process transformed this remote mountaintop village into a mecca for tourists seeking adventure and a piece of history under their skin.

DUTERTE THREATENS TO DETHRONE THE JEEPNEY AS KING OF FILIPINO ROADs

The New York Times

MANILA — In Alvin Ocampo’s 18-year-old jeepney, the dashboard is held together with yards of peeling electrical tape. The only concession to Manila’s stifling heat is a fan screwed to the ceiling. And unless you count the padlocked metal grate in place of the driver’s-side door that Mr. Ocampo installed after a gang of glue-sniffing teenagers robbed him of a fistful of pesos, the vehicle has no safety features to speak of.

Nevertheless, on a recent Friday afternoon in December, scores of passengers climbed aboard Mr. Ocampo’s jeepney, one of thousands of locally produced passenger trucks that are icons of Manila’s traffic-clogged and pollution-choked streets.

LONELINESS AND THE LOVE DOLL

NBC News

I produced and directed this short documentary about Nakajima, a Japanese man searching for companionship and found love in his sex doll. In this story I found the universal emotions of loneliness and longing for companionship that underpin a seemingly deviant lifestyle.

4:55 minutes

ON THE RUN FROM DUTERTE'S DRUG CRACKDOWN

The New York Times

MANILA — Every morning before dawn, Rosario Perez checks to make sure her sons are still alive. The three brothers, all in their 20s, sleep at the houses of friends and relatives, moving regularly, hoping that whoever may have been assigned to kill them won’t catch up with them.

They are not witnesses on a mob hit list, or gang members hiding from rivals. They are simply young men living in the Philippines of President Rodrigo Duterte.

“How could I not send them to hide?” said Ms. Perez, 47, after peeking in on two of her sons and phoning the third. “We can barely sleep out of fear.”

Nearly a year into Mr. Duterte’s violent antidrug campaign, in which more than 4,000 people accused of using or selling illegal drugs have been killed and thousands of other killings are classified as “under investigation,” fear and mistrust have gripped many neighborhoods of Manila and other cities.

Residents are cobbling together strategies to hide and survive. Many young men are staying indoors, out of sight. Others have fled the urban slums, where most of the killings occur, and are camping out on farms or lying low in villages in the countryside.

in duterte's philippines, having a beer can now land you in jail

The New York Times

MANILA — When six plainclothes policemen, hands gripping their holstered guns, charged down the winding alleys of the slum where Edwin Panis lives, he didn’t imagine they could be coming for him.

Mr. Panis, 45, was drinking beer with friends near his shack on an embankment overlooking Manila Bay. A stevedore and neighborhood security officer, he hardly fit the profile of the drug addicts and dealers who have been targeted by the police since President Rodrigo Duterte took office — a bloody crackdown that Mr. Panis, like many Filipinos, supported.

But in moments, he and his three friends were under arrest, hands cuffed behind their backs. Their offense: drinking beer in public.

“The war on drugs has become a war on drunks,” Mr. Panis said bitterly, days after his release from an overcrowded cell.

a transgender paradox, and platform, in the philippines

The New York Times

MARIA RESPONDO, Philippines — Angel Cabaluna dusted makeup onto her thighs, styled her hair in loose curls and applied smoky eye shadow that glittered on her lids.

As this hamlet of cornfields and concrete houses prepared for festivities honoring its patron saint, and as some people gathered in prayer, Ms. Cabaluna, 20, was primping to compete in an annual transgender beauty pageant.

“This is our passion,” she later said.

Dominated by conservative morals taught by the Roman Catholic Church, the Philippines is also one of Southeast Asia’s most tolerant countries toward gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people. And lawmakers are taking steps to ensure national legal protections that would penalize discrimination against them.

in the philippines, dynamite decimates entire food chains

The New York Times

BOHOL, Philippines — Nothing beats dynamite fishing for sheer efficiency.

A fisherman in this scattering of islands in the central Philippines balanced on a narrow outrigger boat and launched a bottle bomb into the sea with the ease of a quarterback. It exploded in a violent burst, rocking the bottom of our boat and filling the air with an acrid smell. Fish bobbed onto the surface, dead or gasping their last breaths.

Under the water, coral shattered into rubble.

The blast ruptured the internal organs of reef fish, fractured their spines or tore at their flesh with coral shrapnel. From microscopic plankton to sea horses, anemones and sharks, little survives inside the 30- to 100-foot radius of an explosion.

Rodrigo Duterte, Scorned Abroad, Remains Popular in the Philippines

The New York Times

MANILA — Virgilio Mabag figures there is a good chance that his meth addict brother will become a casualty of President Rodrigo Duterte’s deadly campaign against drugs in the Philippines.

“I told him to prepare himself to die,” Mr. Mabag said.

But Mr. Mabag, 54, who runs a neighborhood volunteer association in a sprawling Manila slum, still enthusiastically supports Mr. Duterte, saying that his policies will make the country safer and more orderly.

“I’m delighted,” said Mr. Mabag, who was wearing a Duterte T-shirt. “This is the only time I’ve seen a president like this, who says exactly what he wants to say.”

The rest of the world may have trouble understanding this, but Mr. Duterte still commands ardent support in the Philippines.

IN PHILIPPINE DRUG WAR, DEATH RITUALS SUBSTITUTE FOR JUSTICE

National Geographic Magazine

AS SOON AS Rick Medina saw the body slumped onto the curb on the evening news last November, he knew it was his 24-year-old son, Ericardo. The corpse — dumped on a quiet avenue in the Philippine capital of Manila, with his back to the TV cameras — could have been anyone. But a father knows.

The next morning his daughter Jhoy, 26, went to the morgue. Eight bodies were lined up on the floor, covered in sheets or in body bags. They all died the same way: their heads bound in packing tape, then stabbed multiple times with an ice pick to pierce their lungs. She refused to believe one of them was her brother until she unzipped the final body bag. Jhoy wanted to scream. Instead, she froze.

Ericardo’s body was dumped with a cardboard sign labeling him a drug user. According to his father, Ericardo never touched drugs; Jhoy says he’s dabbled in it. Either way, his killers meted out a final punishment without due process.

On Patrol With Police as Philippines Battles Drugs

The New York Times

MANILA — Officer Kathlyn Domingo walked through a maze of narrow alleys, ducking under jumbles of electrical wires and hanging laundry to the open doorway of a flimsy two-story house made of found wood and rusty nails.

Tough, earnest and carrying a .45-caliber pistol with a pink grip, Officer Domingo, 30, patrols one of Manila’s most destitute slums, Santa Ana. Last month, I spent a night on patrol with her and some colleagues, to see, from their perspective, the Philippines’s deadly crackdown on drug dealers and users.

THE GENERAL RUNNING DUTERTE'S ANTI-DRUG WAR

The New York Times

Gen. Ronald dela Rosa, chief of the Philippine National Police, knows the value of a public display of remorse. He has been forced to apologize more than once.

He was wrong, he acknowledged before the Philippine Senate as TV cameras rolled, to have trusted undisciplined policemen who killed a small-town mayor suspected of dealing drugs, as the mayor lay defenseless on a jail-cell floor.

“I cannot blame the public if they’re losing their trust and confidence in their police,” he told the Senate panel, accepting a tissue from the dead mayor’s son to wipe away his tears.

Heroes of the philippines

National Geographic Magazine

RECUERDO MORCO WAS 22 when he first saw snow. Wrapped in four layers of coveralls and parkas, he looked up into the swirling sky as huge flakes settled onto the deck of his cargo ship.

He carved his girlfriend’s name into the snow and circled it with a heart. Recuerdo had grown up in the Philippines on a tropical island rimmed with white sand and coconut palms. Standing on the cargo ship slicing through the icy waters near the Arctic Circle, snowflakes tickling his face, was a dream come true. “I’m really here,” he thought.

They pulled into the port of Kemi, Finland, in the wake of an icebreaker, jagged blocks of white peeling off the sides of their ship. Recuerdo stepped ashore and went on what he calls the “seaman’s mission”: find the nearest shop and buy a SIM card so you can call your mother.

AS H.I.V. SOARS IN PHILIPPINES, CONSERVATIVES KILL SCHOOL CONDOM PLAN

The New York Times

MANILA — Jhay-ar Tumala remembers sitting in a pew in Manila’s Quiapo Church, holding a sealed envelope with his H.I.V. test results, and praying. He was 19 and had been having sex since he was 15.

“I didn’t know anything about H.I.V. or AIDS,” Mr. Tumala, 23, said last week. He does not remember reading about it in the papers or learning about it in school. And he had used condoms only intermittently.

The envelope contained bad news.

His story is not unusual, and that may also mean bad news for the Philippines.

DUTERTE'S FREE BIRTH CONTROL ORDER IS LATEST SKIRMISH WITH CATHOLIC CHURCH

The New York Times

MANILA — When Lizel Torreras, 35, became pregnant with her third child, she mixed a tincture of bitter herbs and mahogany bark, a home remedy said to induce abortion. Her husband, who worked as a garbage scavenger, did not make enough money to buy a regular supply of birth control pills, much less raise another child.

“With just two kids, we were already struggling,” she said. “The children were going to have a hard time. We might not have been able to send them to school.”

But after three attempts, Ms. Torreras, a churchgoing Catholic, could not bring herself to drink the potion.

Like millions of other women in the Philippines who have no access to contraception, Ms. Torreras had the baby. Then another one.

A Last Holdout on Divorce, Philippines Tiptoes Toward Legalization

The New York Times

MANILA — Lennie Visbal last saw her husband, Joel, 13 years ago. Even then, she said, “it was like looking at a stranger.” But since divorce is not possible in the Philippines, Ms. Visbal can’t escape him.

“I’m in limbo, I cannot move,” Ms. Visbal said. “Every time, there is a reminder that I’m legally attached to him.”

The Philippines is the only country in the world, aside from Vatican City, where divorce remains illegal.

PHILIPPINES MOVES TO SHUT MINES ACCUSED OF POLLUTING

The New York Times

CLAVER, Philippines — The Philippine mining town of Claver is busy with bakeries, fruit stands, pool halls and karaoke bars. In the mountains nearby, bulldozers cling to treeless slopes, scooping out red soil and leaving gaping pits. On the horizon, cargo ships wait to bring nickel ore to China.

Many here are afraid that none of this will last.

“If the mines go, then the jobs are gone too,” said Jayson Reambonanza, 31, who drives a dump truck for one of the area’s many nickel mines.

The Philippines, which exports more nickel ore than any country in the world, is in the midst of a wide crackdown on mines accused of violating environmental protection laws.

THE BAR GIRLS OF ANGELES

KCRW's Unfictional & The Groundtruth Project

—Winner, regional Edward R. Murrow award for news documentary, 2017

While covering Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, amid the destruction that killed thousands and displaced millions, an aid worker told me a truth about disasters that haunted me long after I left. First comes the humanitarian aid, she said, then come the human traffickers.

Two years after Haiyan, I went to Angeles, a notorious, crime-ridden red light city to spend time with sex workers driven to the trade after the typhoon. The reporting was a feat in gaining access and trust. The resulting story is a sensitive, nuanced portrayal of the interplay of disasters, trafficking, sex work and poverty.

I conceptualized, reported and scripted this radio documentary with funding from a Groundtruth Climate Change Fellowship.

28 minutes

Death rituals help restless spirits find peace in the Philippines

National Geographic Magazine

“We can’t move on unless we see her,” Tudo’s aunt, Nancy Dinamiling, said. “Unless we see her corpse, we can’t believe it’s true.”

Back in Umalbong, a group of Tudo’s cousins held a ceremony that blended Roman Catholic prayer with Ifugao ritual. Gathering in a circle, they ritually slaughtered a pig and prayed that Tudo’s spirit would help searchers find her body. On the seventh day of prayers, Tudo spoke to her cousins through a seer, a woman who served as a conduit between the living and the dead.

Please find me, Tudo implored her cousins. I’m hanging on a post; I’m missing a foot. My cousin doesn’t have a head. I screamed for my mother. I died slowly. I started praying the Our Father. Before I finished, I was taken.

The next day at the landslide site, a backhoe operator dug into the soft earth and pulled up a pink blanket that had belonged to Jasmin Banawol, the pastor’s wife and Tudo’s cousin. Family members dug out her body. As foretold in the ritual, she had been beheaded by the force of the landslide. A few days later, they uncovered Tudo’s corpse.

FOR ISOLATED PHILIPPINE TOWN, A PLANNED ROAD IS A LIFELINE AND A WORRY

The New York Times

PALANAN, Philippines — There is no road to Palanan.

The town, 190 miles northeast of Manila on a stretch of rugged Pacific coastline, is separated from the crowds and chaos of the rest of the Philippines by a three-day trek through tropical jungle, a seven-hour ride on a wooden pump boat or a 25-minute flight on a three-seater Cessna.

Cloistered in the foothills of the Sierra Madre, Palanan’s farmers cross fields on the backs of loping water buffaloes. Children in plaid uniforms walk to school along beaches of white sand. A few motorcycles with sidecars, brought in on boats, rumble through the carless streets of the dusty town center. Carved canoes slide down broad rivers, and narrow outrigger boats bob along the shore.

WHEN HALF A MILLION DRUG USERS SURRENDERED IN THE PHILIPPINES, AUTHORITIES SENT SOME OF THEM TO ZUMBA

PRI's The World

It didn't work. I visit a neighborhood struggling to deal with the drug problem, with no resources and little government support. The resulting rehabilitation efforts fell short, and their neighbors turned up dead.

5:09 minutes

THE WAR ON DRUGS IS LEAVING HUNDREDS DEAD IN THE STREET

PRI's The World

After Rodrigo Duterte became president, I was among the first foreign reporters to cover his bloody anti-drug campaign. I spend the night on the crime scenes at a time when people were still struggling to make sense of the massacre unfolding in Manila.

5 minutes

THE CANDIDATE THAT'S OK WITH RAPE AND DEATH SQUADS MAY BE THE NEXT PRESIDENT OF THE PHILIPPINes

Vice News

Duterte is a controversial figure who has risen in popularity by billing himself as an anti-establishment outsider who would upend traditional Philippine politics — an everyman who offends polite sensitivities, but is attuned to the frustrations of people deeply disaffected with politicians they view as more interested in enriching themselves than addressing the needs of Filipinos. That's helped propel him to 33 percent in polling released last week, ahead of Mar Roxas, supported by the current administration, with 22 percent.

It would be easy to compare him with another presidential candidate who has risen to the top of the polls by saying outrageous things, Donald Trump. But not even the American tycoon can match Duterte for the shock value of his statements. Trump, for example, never threatened to personally kill anybody. Duterte had no problem doing that.

During a rally on May 1, 2016, the mayor of Davao rambled affably into a microphone, dropping lines like, "They must stop fucking the Filipino."

MAKING THE WORLD'S FIRST PROSTHETIC LEG FOR AN ELEPHANT

BBC World Service

Mosha is the first elephant in the world to have a prosthetic leg. She lost her leg after stepping on a landmine on the Thai-Myanmar border, but an orthopedic surgeon called Dr Therdchai Jivacate came to the rescue and created a prosthetic leg for her. I visit Mosha at the elephant hospital outside Chiang Mai, where now lives for naps, circus peanuts and stealing candy out of her mahout’s pockets.

5:55 minutes

Rediscovering heritage

Monocle Magazine

Once a colonial city of art deco and beaux arts buildings, Manila was heavily bombed during the Second World War. Few buildings survived and much of what remained was torn down in favour of large scale developments as the city's population swelled to an estimated 12 million. Manila went from being the 'Pearl of the Orient' to a traffic-clogged, infrastructure-poor city saddled with a protracted housing crisis.

Yet the Philippine economy is growing at at a fast rate and Manila is in the midst of the property boom that goes along with it. More than 480,000 sq m of office space was built last year, including seven new commercial projects in the CBD in the fourth quarter alone. Residential properties are also on the rise. While most developments in the city tend to be towering skyscrapers a few developers have parked the bulldozers and are instead finding value in Manila's heritage buildings.

the mastermind

The Atavist

I contributed reporting in the Philippines for this investigative series and book by writer Evan Ratliff about a vicious international crime boss whose dealings spanned the globe from his base in a leafy compound in Manila. Many of the most dramatic murders, heists and characters happened in the Philippines. With persistent and tenacious reporting, I tracked down witnesses, prisoners, murder case files, crime scenes and government agents, uncovering previously unknown characters and events.

WHY CONTRACEPTION MAY BE A WAY OUT OF POVERTY FOR FILIPINO FAMILIES

PRI's The World

The slums of Tondo are the most notorious in Manila, and Ana Lisa Loste lives in the most destitute district. Her house is down a long road, permanently muddy from the black goo that drips out of garbage trucks, past the part of the slum where scavengers sort through glass bottles, right where the smell of rotting trash meets the stinging smoke from a field of crude charcoal kilns.

The Philippines has one of the highest birth rates in Asia, and most of the population growth has been in the poorest families who can least afford birth control — or children. In Tondo, people are painfully aware of the irony in this. Around here, it’s not unusual for a woman to have eight or ten children.

5:27 minutes

sleeping with the enemy: a martial law love story

Esquire Philippines

When the Philippine dictator Marcos fell, my stepfather, heir to the military dynasty that protected Ferdinand and Imelda's power, escaped into exile with them. My mother — a journalist who saw her brother and husband jailed for political dissidence, her nephew shot through the chest at a protest rally, people she knew killed and tortured — cheered in the streets. Today, they're the sweetest couple you'll ever meet. It's a story about politics during a dramatic chapter in Philippine history, and finding love in the time of exile.

AN AMERICAN AND HIS DOG HELP BRING CLOSURE TO SURVIVORS OF TYPHOON HAIYAN

PRI's The World

More than 6000 people died in Typhoon Haiyan. Thousands of bodies were never found or identified. Four months after the storm you'd expect a person might start to accept that his missing loved ones have died. But it doesn't always work that way. I follow a team of cadaver dogs as they search for remains of the typhoon's victims.

5:27 minutes

TURNING A MILLION YARDS OF POST-TYPHOON TRASH INTO JOBS

NPR News

After the Typhoon Haiyan cut of path of destruction through the Philippine city of Tacloban, I follow the "disaster garbage man," a waste management specialist working to turn rubble into jobs.

5 minutes

i visited tacloban soon after typhoon yolanda hit

VICE

[...] The next day we drove into Tacloban just as the sun was going down, in an ambulance with the curtains drawn. Everyone was peeking out of the windows, not talking as the scenes of destruction got worse and worse. Before we got to Leyte, the island where Tacloban is the capital, we already felt bad. We’d seen the footage and heard the reports. But actually being in the presence of the destruction is much different. It never ends. It’s not a minute-long video clip before the newscaster switches to a different story. There were piles of rubble covered in mud on either side of the road. There wasn’t a single house that wasn’t damaged or completely destroyed. Coconut trees and cement lampposts were snapped in two. This coast was in the direct path of Typhoon Yolanda, and the few people left were living in the rubble of their old homes, starting fires for light, and waiting for someone to show up with food or water.

Shev was the only one who hadn’t heard from her family. The last time she heard from them was at 6 AM on the day of the typhoon, when her mom texted to say they were fine. That was four days ago, before media started reporting death tolls at 10,000 and she caught a glimpse of her house on some aerial footage. Nothing was left except the cement floor. Shev didn’t look out the window. She pulled a blanket over her head and put her face in her hands.

MAGGI: THE LOCAL SEASONING FROM EVERYWHERE

PRI's The World

Immigrants from countries as far flung as Nigeria, Mexico, the Philippines and Poland share a common ingredient. They all use Maggi, and they all insist it belongs to them. I talk to cooks from immigrant communities around New York City about how Maggi reminds them of home, and upset a few people by revealing where it's really from.

4:54 minutes